Well, I'm not an old-timer (yet, I think?), but I do consider myself fortunate to have grown up in a time where the Internet was still in its infancy and not a household word, and where the only ways to pursue knowledge on herps was through books, magazines, and resources of that nature. I love the Internet. I think the Internet was the best thing to happen to the developed world. But the Internet contains so much information - endless, in fact - that it's hard for me to imagine opportunities for kids today to use investigative skills to unlock intriguing information that formed the basis of daydreams I had as a kid. Information is consumed only as fast as one can receive it, and as a kid it was slow and steady. There was much more time for reflection then than there is today. Maybe someone will read this and completely disagree with that statement. Maybe I'm wrong. Cognitive bias or not, there's no refuting the value of good old-fashioned hard-copy literature in the days when it was the end-all-be-all for rabid curiosity-seekers.

As a young kid, I had some of the older, tiny pocket field guides like the Golden Guides. I read them over and over again until the cover and/or back fell off. In retrospect, the information contained within them was very basic. To me, it was more about looking at the drawings of snakes I hoped to find someday.

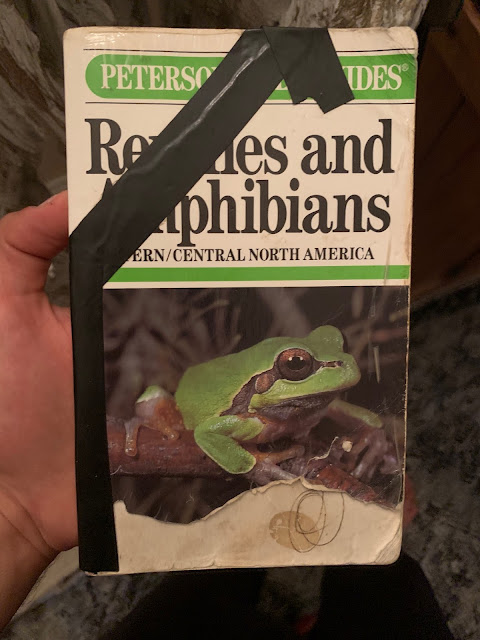

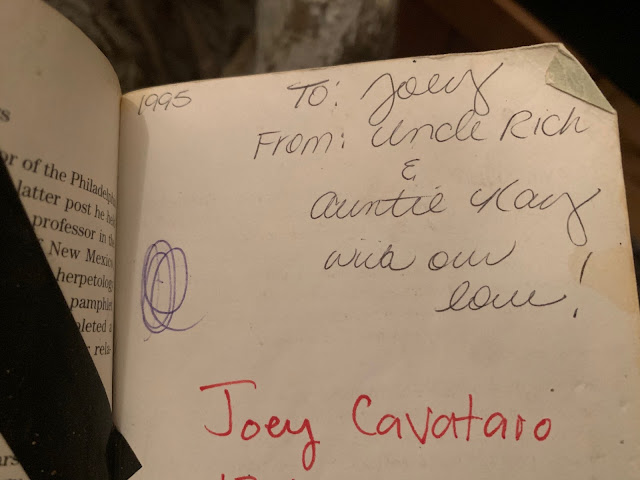

But one particular book changed my outlook on herping forever. It was gifted to me by my Uncle and Aunt from California, for my birthday in 1995. It was the third edition of the Peterson Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern/Central North America, by Roger Conant and Joseph Collins. My precious new acquisition was brand new and tightly-bound, and on the cover was an iconic photograph of a pine barrens tree frog. I was so excited I could barely contain myself. I probably ran off with it and shut the door to my room so as to block any distractions that would impede my fantasies.

In fact, the book came in handy A LOT. I took it everywhere I went, even on trips where I wasn't expecting to go herping. I took it just in case. Every time I traveled somewhere new, I'd take it in hopes of using it to help identify species new to me. It became my Bible - the field herper's Bible. It was the final word when it came to searching for, identifying, handling, and recording herps.

Of course, over time, I became quite proficient at identifying herps - so much, that I found that I was using the field guide less and less. You can only use it so much when you're traveling throughout the Midwest. The book set out to teach me and it succeeded. It never was in jeopardy of leaving my possession - to this day it occupies a very prominent place on my bookshelves. It stands next to a book that I consider to be far inferior - the fourth edition of the same publication (long story but it's a mess of a book). I love my old copy of the third edition. It's like an old friend that wants to remind me of the carefree days when I was a kid spending hours catching frogs and snakes. It's the only book I own with snake musk and toad urine stains in it.

I think the point of this post is that material goods are always secondary to experiences, but do not underestimate the inspiration that may be sparked by a good book. The effect this book had/has on me transcends paper and ink and glue.